The disinformation fallout of a fake nuclear attack

Summary

This article explores nuclear disinformation in the India-Pakistan context, with a focus on the April-May 2025 tensions, during which false claims circulated about a radiation leak and an attack on a nuclear facility. It examines the high stakes of nuclear threats, the legal grey zones in which such disinformation spreads, and practical steps the public can take to help prevent escalation.

Introduction

April 2025’s India-Pakistan conflict saw false claims and reports — backed by misappropriated video game footage, AI-generated content, and digitally manipulated images — widely circulated both in the media and online. These included fabricated reports of a radiation leak in Pakistan and an alleged Indian attack on a Pakistani nuclear facility. This post examines these claims and discusses disinformation in the India-Pakistan context.

The 2025 crisis

On 22 April 2025, armed militants attacked Hindu tourists in Indian-controlled Kashmir, killing 26 civilians and injuring more than 20. The attack occurred along the Line of Control, a de-facto border between India and Pakistan, which demarcates their control over Kashmir. Initially, according to a number of reputable sources, it was claimed that The Resistance Front, an off-shoot of the Pakistan-based Islamist militant organisation, Lashkar-e-Taiba, had claimed responsibility via the Telegram messaging app. However, we could not independently verify the existence of this post and have not been able to view the original message. At the time of writing, no group has officially claimed responsibility, and the Indian government has not accused any particular group or entity of carrying out the attack.

Prime Minister Modi strongly condemned the attack, declaring that “those behind this heinous act will be brought to justice.” The Indian government accused Pakistan of helping to orchestrate the attack — a claim which Pakistan vehemently denied. Pakistan has historically sponsored non-state armed groups as a cost-effective way to counter Indian influence and offset its lack of strategic depth. This pattern has led successive Indian governments to blame Pakistan for terrorist attacks, with Modi stating that his government will no longer differentiate “between the government sponsoring terrorism and the masterminds of terrorism.”

In retaliation, India launched ‘Operation Sindoor’ on 6/7 May, conducting airstrikes against what it termed “terrorist infrastructure” in Pakistan and Pakistan-controlled Jammu and Kashmir. This marked the beginning of the latest bout of conflict between India and Pakistan. After four days of fighting, a tenuous ceasefire agreement brought the nuclear powers back from further escalation. Though brief, this crisis was deemed by the Council on Foreign Relations to be “the most significant bilateral confrontation since 2019”.

Disinformation on the digital frontline

While missiles illuminated the night sky, another war was being waged online. Armed with keyboards, repurposed war clips, and footage from video games such as Arma III, Indians, Pakistanis, and other interested parties battled for control of the digital narrative. Their metric of success was not territory or casualties, but dominance of social media platforms, including Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, and X (formerly Twitter) (for more, see 1, 2, 3).

Last year, the World Economic Forum ranked India as the country most at risk from disinformation and misinformation, with Pakistan exhibiting comparable susceptibility to these threats. Social media platforms amplify disinformation through viral algorithms that prioritise engagement over accuracy. As fact-checking lags and AI-generated fakes rise, misleading content spreads faster - especially during crises such as this one in South Asia.

As the pixels settle and these digital combatants lay down their phones, fact-checkers, analysts, and journalists have begun combing through the wreckage of the chaos that occurred online and in traditional media. Delhi-based fact-checker Uzair Rizvi, commenting on the immense volume of disinformation that was circulated, stated: “This situation felt as if a month's worth of disinformation bombarded social media within the first few hours.” Similarly, Joyojeet Pal, an Associate Professor of Information at the University of Michigan, remarked: “The scale went beyond what we have seen before," adding that "this had the potential to push two nuclear powers closer to war.”

Heightened nationalist sentiment fuels disinformation and creates a feedback loop of polarisation that amplifies extremist voices, marginalising moderate viewpoints and drowning out calls for peace. In the short term, unchecked discourse on social media and in traditional press can escalate tensions, compelling governments to take actions they might otherwise avoid under normal circumstances. This can lead to violent outcomes, ultimately serving the interests of extreme elements. Governments and/or government-backed agencies are also increasingly engaging in disinformation campaigns to meddle in foreign affairs, suppress dissenting voices and discredit political opponents.

Rampant disinformation was not confined to social media platforms, with traditional press also spreading false claims and fabricated reports. Citizens for Justice and Peace (CJP), a Mumbai-based human rights organisation, filed a complaint against six of India’s most popular mainstream news channels to the News Broadcasters and Digital Association (NBDSA), for serious ethical breaches, namely, “the use of misleading visuals, sensationalist commentary, and theatrical framing to manipulate public perception.” Earlier this year, the CJP filed a similar complaint that led the NBDSA to direct two news channels to remove segments of their Israel-Hamas conflict coverage that violated broadcasting guidelines.

With limited verified updates and near-complete information blackouts in some areas, social media became the frontline of a digital war. Users of X received competing stories — each amplified domestically but often discredited abroad.

In India, social media feeds and TV news splashed unverified “exclusive” reports of Pakistani losses - jets and drones downed, military bases destroyed, generals arrested. Grainy, cinematic footage - later identified as fake - spread across platforms (example, 1, 2, 3, 4). Even India’s Defence Ministry issued clarifications to counter the viral misinformation.

In the example below, Times Now Navbharat – a Hindi news channel with a large viewership – reported that Indian forces have entered Pakistan and captured Karachi port, neither of which actually occurred.

In Pakistan, media and social networks questioned the Indian narrative. Posts and reports circulated suggesting that the Pahalgam attack was a false flag operation staged by Indian agencies to justify retaliation. Around 23,000 tweets supporting the #FalseFlagIndia conspiracies were recorded by early May, with most rhetoric focusing on Muslim persecution in “Modi’s India” and Al Qaeda urging Indian Muslims to “jihad” against India. Deepfakes and AI-generated confessions from “Indian agents” appeared online and were echoed by state outlets.

In a particularly bizarre moment, the official X account of the Government of Pakistan shared footage from the video game Arma III, claiming that it showed a Pakistani Close-In Weapons System engaging an Indian fighter jet. The post, which currently remains online, has more than 2.4 million views.

Although it may not meet the traditional kinetic threshold of armed conflict, the scale, intent, and impact of these operations have led some analysts to classify them as a form of digital warfare. By actively seeking to influence adversarial decision-making, shaping public perception, and provoking strategic responses, such campaigns increasingly blur the line between information operations and war.

So how was this supposed fallout fabricated exactly?

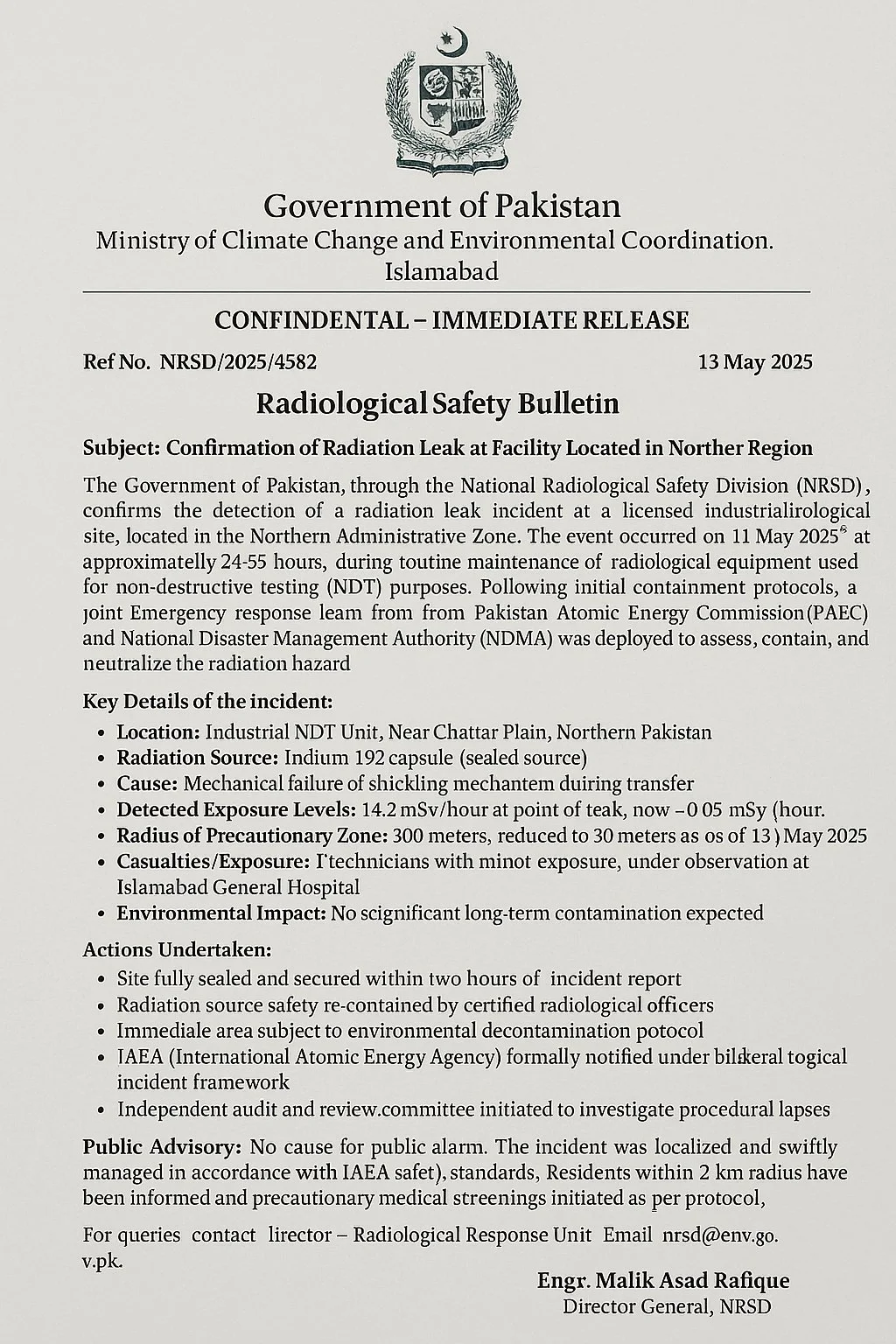

On 13 May, a document titled “Radiological Safety Bulletin” began circulating online. Purportedly issued by Pakistan’s National Radiological Safety Division, it warned that a radioactive leak had been detected at a “licensed industrialirological [sic] site, located in the Northern Administrative Zone”. However, riddled with errors, the document is clearly a fabrication. Below is the original text alongside our annotated version highlighting the most obvious mistakes:

At a glance, the document looks official. Had its author given a bit more attention to their spelling and grammar, it might even pass as somewhat believable. Nevertheless, despite being clearly fake – even to the untrained eye – the document reached millions of users across various social media platforms, amplified by prominent influencers and verified accounts (example 1, 2, 3, 4).

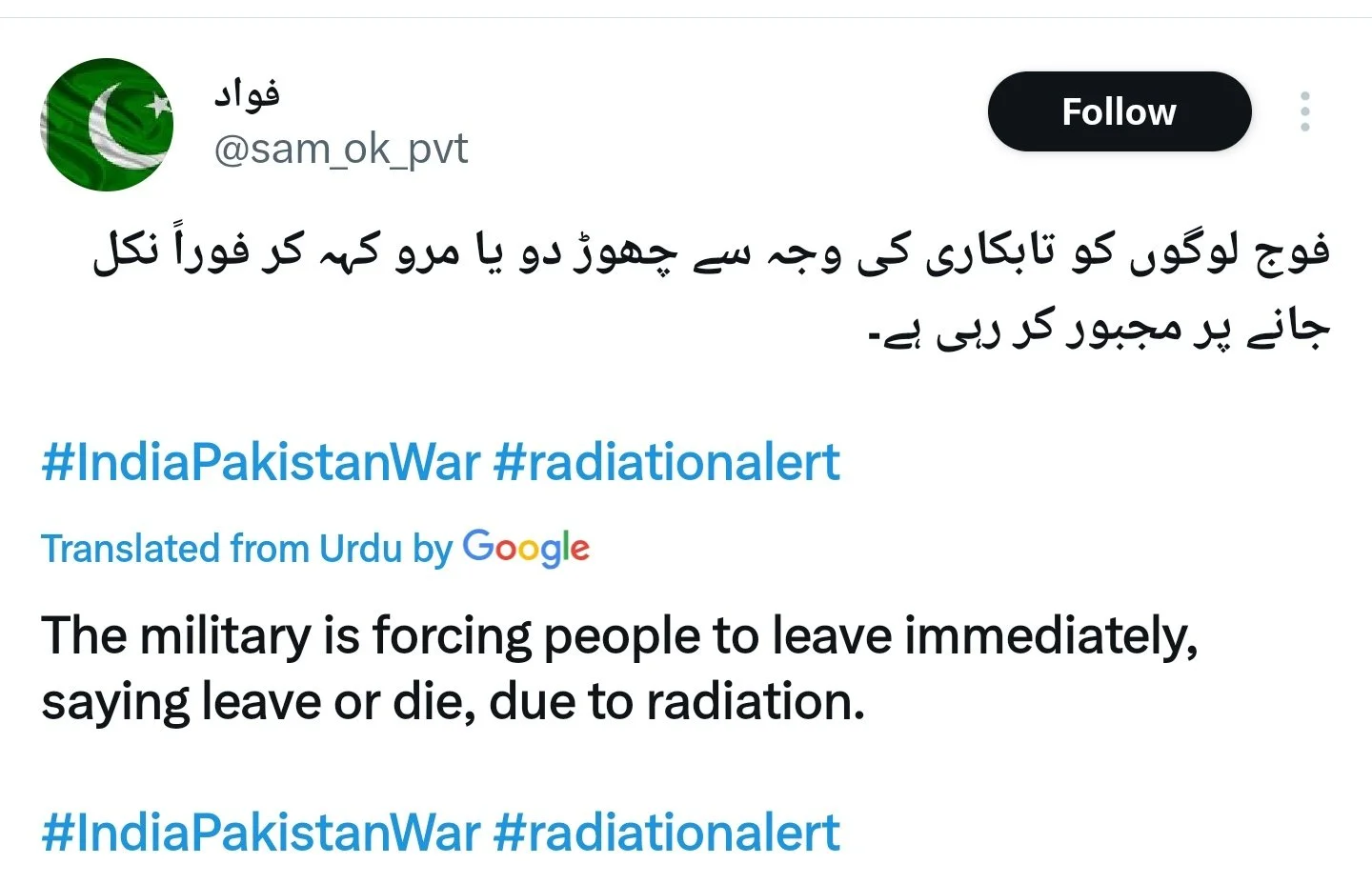

The document was soon accompanied by false reports of people exhibiting symptoms akin to radiation sickness, with some users accusing the Pakistani government and military of suppressing information. For example:

Two widely circulated posts claimed to come from a user living in the affected area, who alleged witnessing military-led forced relocations due to a radiation leak.

The account has since been deleted, with some users suggesting that the Pakistani flag in the profile picture was little more than a thin veil for someone likely based elsewhere (example, 1, 2, 3, 4). Within an hour of witnessing the evacuation, the account began posting some peculiar replies to other users...

It is also noteworthy that this was not an isolated hoax. Rumours spread that India had targeted a nuclear site in Kirana Hills, causing a radioactive leak; the International Atomic Energy Agency refuted the claim. But by then, the misused satellite imagery had trended across X.

This arguably had the most potential to cause highly dangerous escalation in the conflict. By simulating a nuclear emergency, the bulletin risked triggering panic, retaliation, or international alarm. For two nuclear-armed states, such narrative manipulation crosses into precarious territory.

Historical patterns of information warfare: India-Pakistan

This was not the first-time mis- and disinformation played a role in India-Pakistan conflict escalation. India and Pakistan have fought four wars since Partition in 1947, with Kashmir remaining the key flashpoint. Since both became nuclear powers in 1998, their confrontations have evolved, shifting from large-scale warfare to cross-border strikes, insurgency, and now, information warfare.

The 1999 Kargil War and the 2019 Pulwama-Balakot Crisis displayed similar use of disinformation, selective framing, and emotionally charged propaganda to contort public opinion and international perception. In both instances, each state looked toward the ‘good-guy-bad-guy’ trope to frame itself as the victim and the other as the aggressor, laying the groundwork for what would intensify in 2025.

Both India and Pakistan have refined their use of disinformation, not just to boost domestic morale, but to gain diplomatic leverage. As digital tools and AI become more accessible, official messaging increasingly overlaps with manipulative online campaigns, blurring the line between state communication and psychological operations (PSYOP). These strategies go beyond the simple dissemination of false information, aiming instead to subtly reshape how entire populations think and, consequently, behave. By leveraging increasingly sophisticated psychological techniques and information technologies, states are engaging in what resembles “cognitive warfare” – targeting public opinion not just to mislead, but to influence policy outcomes and destabilise trust in institutions.

As one report observed during the May 2025 crisis, “coordinated misinformation and disinformation campaigns were evident on both sides, with Indian pro-government influencers openly framing it as ‘electronic warfare.’ Indian mainstream media outlets played a significant role in amplifying false claims…” In Pakistan’s case, Business Today noted a “digital onslaught – an orchestrated campaign of disinformation and psychological warfare … aimed at shaping global perception,” adding that “the incident exposed the deepening reliance on digital psyops as a tool of modern conflict.”

The edge-of-your-seat nature of viral content contributes to conflict escalation: platforms optimise for emotional engagement, pushing for digital outrage to spread faster than any diplomatic response can be marshalled. As one analysis warns, “once these narratives harden, they shape public mood, embolden military responses, and close off diplomatic exits.”

Information warfare in India-Pakistan conflicts typically follows a cyclical pattern: a triggering event (often an attack or skirmish), followed by mutual accusations, then a trial by media online; this has also been referred to as a ‘disinformation feedback loop’. India and Pakistan governments both have cyber cells and media arms that unofficially or semi-officially engage in narrative amplification. Coordinated botnets, nationalist influencers, and diaspora-linked accounts have played a central role in amplifying polarising narratives. These actors often weaponise hashtags and political rhetoric to manufacture outrage, dominate online discourse, and escalate tensions in real time, as was also noted in an ArXiv study of the 2019 Pulwama crisis.

These narratives are not just spontaneous. They can delegitimise international mediation efforts, influence public opinion at home, and signal strength abroad. The 2025 conflict further impresses upon us that digital disinformation is not just a social media problem; it is a security threat that can be easily used to sway support because there is no rulebook (yet). Importantly, while disinformation alone is unlikely to directly lead to a nuclear attack, it can contribute to a heightened state of mistrust and miscalculation. This is particularly risky given the asymmetry in nuclear postures: India maintains a No First Use (NFU) policy, while Pakistan does not, reserving the right to use nuclear weapons first in a conventional conflict. This asymmetry means that information warfare could lower the nuclear threshold unintentionally and “create a nuclear confrontation between India and Pakistan - i.e. under conditions of extreme conventional imbalance or perceived existential threat, use of tactical nuclear weapons may be considered.

Of course, fake news would not trigger nuclear war on its own. However, rapidly evolving digital narratives can amplify tensions, complicate decision-making, and reduce the time available for de-escalation — especially when one side is doctrinally prepared to strike first. Disinformation can spiral into hard policy in minutes, and in such an environment the absence of institutional safeguards against disinformation becomes a serious vulnerability.

The legal vacuum: who is accountable for digital lies?

Currently, no binding international legal framework prohibits states from engaging in information warfare. This legal grey zone enables countries like India and Pakistan to weaponise digital narratives without fear of formal sanctions.

While international law restricts the use of force and coercive intervention, “propaganda and influence operations are … not prohibited”, making narrative manipulation a lawful form of statecraft. The Tallinn Manual 2.0, a key interpretative guide for cyber operations, classifies election meddling and narrative manipulation as ‘interference’, and not a breach of sovereignty unless it involves coercion. Current interpretations of sovereignty in cyberspace lack clarity when applied to psychological or influence operations, making enforcement difficult. The Budapest Convention focuses on cybercrime, not state-sponsored information warfare. Efforts such as Microsoft’s proposed Digital Geneva Convention - a draft framework to protect civilians from cyberattacks, including disinformation, during times of war - remain largely aspirational. As a result, some states operate with impunity.

The India-Pakistan radiation leak hoax especially offers a particularly stark case study of how digital disinformation may potentially be seen as a weapon in itself, capable of disrupting diplomacy, worsening conflict, and undermining nuclear stability.

If there is no enforceable legal regime for state-led digital misinformation, these tactics will remain viable tools for psychological and strategic advantage. In regions like South Asia, where nuclear capabilities make miscalculation catastrophic, this is not just a communications issue – it is a global security concern.

What now? The need for digital peace architecture

Moving forward, policymakers and researchers must advocate for several interlocking reforms to address this legal lacuna.

First, bilateral protocols for digital escalation control should be established to mitigate misunderstandings. The United Nations OEWG in 2021 strongly recommended confidence-building measures (CBMs), including the creation of national Points of Contact to assist crisis communication and reduce the risk of escalation through misperceptions or disinformation (UN OEWG Report, 2021, pp. 6–7, §§41–47).

Second, multilateral agreements on information warfare norms should be pursued – the UN’s 11 non-binding norms for responsible state behaviour in cyberspace offer a strong starting point. The OEWG affirmed that international law applies to cyberspace but also recognised the need for further common understanding and potential future legal instruments to define and regulate harmful digital conduct (ibid., §§24–29, 34–36).

Third, regional fact-checking partnerships, similar to the EU’s ‘EuvsDisinfo’ initiative, could help rapidly debunk viral misinformation during crises and create public trust in verified information.

Lastly, there is a growing international consensus, reflected in the OEWG and prior GGE (Group of Governmental Experts) reports, that the status quo is unsustainable. While norms have been helpful, the lack of binding frameworks allows states to weaponise digital information systems without accountability. The OEWG called for “continued discussion on the elaboration of rules, norms and principles” and stressed the urgency of exploring new instruments that go beyond voluntary measures (A/AC.290/2021/CRP.2, §§33, 77).

Until strong frameworks exist, the world remains vulnerable to the next viral lie that could spark very real, very grave consequences.

However, such legal infrastructure may take years, if not decades, to materialise. But while policymakers deliberate, we, as netizens, are not powerless. Collective digital responsibility can slow the spread of manipulation and protect the fragile space for diplomacy. Here’s what we can do, now:

Pause and verify before sharing. If something evokes strong emotion – fear, outrage, euphoria – take a moment. Check the source. Use tools like reverse image search, metadata trackers, or consult trusted fact-checking organisations before forwarding or reposting.

Diversify your information sources. Follow reputable outlets across geographies and ideological lines. A global, plural feed is the best way to avoid getting trapped in a partisan echo chamber.

Report, don’t amplify. Even if you disagree with or intend to critique a piece of disinformation, resharing it gives it oxygen. Instead, report it to the platform.

Support fact-checkers and media literacy work. Engage with organisations that track, debunk, and educate, especially during crises. Share their verified content. Help their work reach further.

Talk about it. Speak to peers, families, classrooms, and networks about disinformation. Awareness is our collective defence; informed communities are harder to manipulate.

In an age where a fake nuclear leak can trend before facts can catch up, each of us becomes part of the firewall – or the fuel. Choose wisely.