Pentagon Pizza Tracker Part I: The Problem of Pattern-Seeking

Have you heard of ‘Pizzint’? Can it really predict a nuclear attack? There is a good chance you have found this blog because someone recently mentioned the Pentagon Pizza Tracker to you. However, before we decide whether late-night pizza orders can signal global catastrophe, we need to step back and ask a more fundamental question: what actually turns information into intelligence?

As researchers, allow us to start with some background to the theory, because this distinction is where many discussions around ‘Pizzint’ — and OSINT more broadly — go wrong. People very often confuse the use of open-source information with Open-Source Intelligence (OSINT). However, information ≠ intelligence. What really matters is the ability to tell the difference between a useful signal and confusing noise.

What is a signal?

A signal is a piece of actionable or insightful information that can be extracted from open-source data; it reveals something genuine about a situation, a trend, or an individual. For example, a geolocated social media post that reliably shows the movement of strategic vehicles. Noise, on the other hand… covers pretty much everything else: information that is irrelevant, misleading, or distracting, bits and pieces that do not advance understanding. This includes rumours, coincidences, unverified claims, and even real data taken out of context. Crucially, noise can obscure genuine signals, making analysis harder and leading us down false paths.

French philosopher Jean Baudrillard already mused about this issue a century ago. He wrote about representations that no longer point to reality, but instead circulate as self-contained signs, detached from the actual events they were once supposed to illuminate. The elimination of the real world. In other words, once the pizza delivery theory was picked up and shared, it became a “truth” in itself – regardless of whether it does or does not reflect reality. More recently, American digital information scholar N. Katherine Hayles has made a similar point. She argues that once information is abstracted from its material source, it takes on a life of its own. In her posthuman framing, the signal itself becomes more important than the context from which it originated. That is exactly what we see with Pentagon Pizza speculation: fragments of open data that morph into memes, driving interpretation, which can continue even when they no longer correspond to the events they claim to represent.

Conversely, what constitutes a signal is not necessarily fixed; it depends on your question, context, and ability to verify sources. A clever insight can be a signal in one frame but noise in another. Meanwhile, uncritical repetition of “clever signals” can turn them into myths or memes. Ordinary cultural signs can be elevated into legendary symbols once they are folded into larger narratives of power. So, a pizza delivery, trivial in itself, becomes a story about Pentagon secrets when viewed through the lens of open-source surveillance.

We want patterns, we need patterns

Intelligence speculation is not just a matter of data; it is also a psychological phenomenon. Humans are wired to seek patterns and stories, even in seemingly random events. ‘Apophenia’ (from the Greek ἀποφαίνειν, ‘to show, or make known’) is the tendency to see meaningful connections between things that are not actually related. This is also where the concept of confirmation bias comes in. Analysts may unconsciously favour evidence that supports their prior beliefs, connecting dots that are not actually linked while ignoring inconvenient contradictions. This dynamic is evident in spurious correlations. A classic example would be that increased ice cream consumption results in more shark attacks. Ice cream is not irresistible to sharks; instead, it is the fact that in the summer, more ice cream is purchased due to the heat, which also results in more people wanting to go swimming.

To many, tracking pizza may fall into this categorisation. While patterns may or may not exist, what stands out about the Pizza Theory is its long history. Namely, the notion of using unusual patterns of civilian activity as informal signals of governmental or military alert status draws on long-standing Cold War probabilistic indicator-and-warning practices in strategic intelligence. During the Cold War, intelligence services developed extensive systems for cataloguing and analysing “indicators” — low-level signals such as troop movements, mobilisations, logistical preparations, or shifts in diplomatic behaviour — that might warn about major geopolitical events or crises. However, in the absence of credible archival or documentary evidence, the idea of Soviet agents literally lurking near pizzerias remains hotly debated. Rather, the persistence of this narrative reflects broader Cold War practices of indicator-and-warning intelligence, in which analysts sought to infer impending crises from low-level signals and patterns of activity.

The Pizza Tracking phenomenon first garnered significant public attention on 1 August 1990, when Washington DC’s pizzerias noticed a record-breaking spike in deliveries to US government installations, most notably the Pentagon. The next day, Iraqi tanks rolled into neighbouring Kuwait. Local pizza mogul Frank Meeks boasted to the LA Times that on the eve of the invasion, his franchises had delivered dozens of pizzas to the Pentagon and fifty-five to the White House. “The news media doesn’t always know when something big is going to happen, but our deliverers are out there at two in the morning”, said Meeks. A follow-up in TIME magazine, comedically entitled ‘And Bomb The Anchovies’, quoted one pizza delivery runner who noted that the pattern had precedent: “Pentagon orders doubled up the night before the Panama attack; same thing happened before the Grenada invasion”.

Eight years later, the pizza delivery record was broken. During the impeachment hearings of former President Bill Clinton, deliveries skyrocketed as White House and Congressional staffers burned the midnight oil. “It's going haywire,” remarked Meeks, who had once again been called upon for his expert insight. The turmoil caused by the Clinton-Lewinsky affair both started and ended with pizza: according to Ms Lewinsky’s testimony, she had pizza on her jacket when she first kissed the president, as they shared a few slices together in the Oval Office during the 1995-1996 federal government shutdowns.

The armchair intelligence era

Hunting for patterns is what happens when we engage in ‘armchair intelligence’. Our fast, intuitive ‘System 1’ thinking jumps to patterns and stories, while the slower, more deliberate ‘System 2’ is supposed to question them. It is much easier to spin a narrative from a few screenshots than to take the time to weigh up the evidence. Consequently, self-awareness is crucial here: the more skilled one is at spotting patterns, the more vigilant one must be to avoid making connections that are not linked.

However, simply being aware of this human tendency is not enough – experienced analysts still fall into these traps. We must examine structured analytical processes. Techniques like systematically comparing competing hypotheses or deliberately considering alternative explanations help keep cognitive shortcuts in check. This allows us to turn raw data into genuine insight instead of just feeding your brain’s love of patterns.

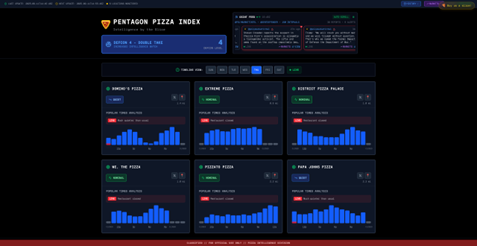

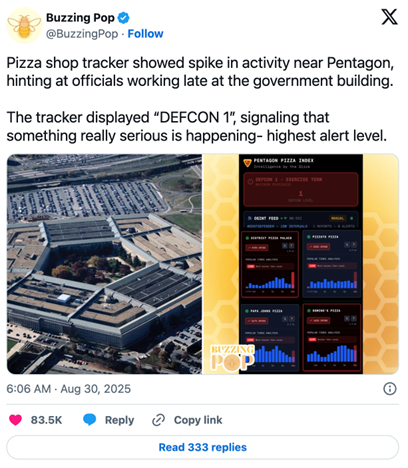

So, data is key. ‘Pizzint’ enthusiasts are no longer reliant on Frank Meeks for their insights. Using Google Maps’ ‘Popular Times’ feature, they can now track in real time the footfall at pizzerias near the White House and Pentagon, turning late-night orders into viable data points. What once rested on rumour and anecdote is now reinforced by quantifiable signals drawn from everyday location data. The ‘Pentagon Pizza Index’ website uses Popular Times data in a dashboard that tracks six pizzerias near the Pentagon. Spikes in restaurant traffic are highlighted and translated into a tongue-in-cheek DEFCON-style alert system. In this way, the site turns a Washington legend into a live experiment in crisis monitoring.

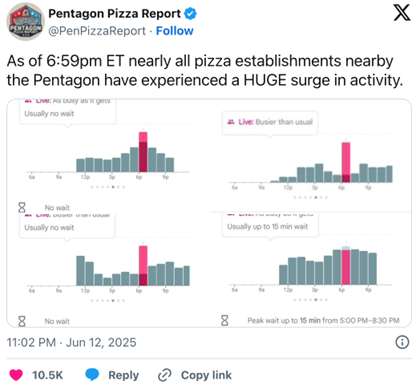

Popular X (formerly Twitter) accounts such as @PenPizzReport also draw on this data, issuing deadpan ‘pizza intelligence’ reports to their followers whenever things look like they might be heating up. According to the Washington Post, one of the account’s 253,600 followers is General Dan Caine, the current chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

Secretary of War and Pentagon don Pete Hegseth is also familiar with the account and its pressing analysis. In an interview with Fox News correspondent Peter Doocy, he joked about ordering pizza not for hunger but for misdirection: “I’ve thought of just ordering lots of pizza on random nights just to throw everybody off. Some Friday night, when you see a bunch of Domino’s orders, it might just be me on an app, throwing the whole system off. So, we keep everybody off balance.” Perhaps some of the USA’s adversaries also follow the ‘PenPizzReport’ account?

Is it pizza in the sky?

Let’s consider conspiracy theories as well. The abundance of openly available information that many of us have access to can feel like a blessing, but it can also have a two-sided nature. People can easily cherry-pick fragments that fit a narrative, mistaking coincidence for causation or isolated events for patterns. While context is everything, public data often travels stripped of its cultural, temporal, or technical framing, cordially inviting misinterpretation. Moreover, clever insights can be distilled into catchy narratives, spreading faster than they can be verified. The anecdote that a lie can travel around the world before the truth has even tied its shoelaces underlines this point.

Yet, recent events seem to further support the view that pizza-based intelligence is viable. On June 12 and 13, Israel conducted strikes on Iranian military and nuclear infrastructure in an effort to stymie the country’s progress toward developing nuclear weapons. Many were blindsided; however, the pizza monitors knew a delivery was on the way. “As of 6:59pm ET, nearly all pizza establishments near the Pentagon have experienced a HUGE surge in activity”, reported @PenPizzReport – about an hour before Iranian state television first reported explosions in Tehran.

Despite what may appear to be a credible source of intelligence, it is important to remember – as discussed – that humans are wired to connect the dots, even when the dots do not marry up. This impulse is amplified by what media scholars call the “CSI Effect”. In that context, audiences today are trained by crime shows, documentaries, and online sleuthing communities to treat fragments of evidence as if they can tell the whole story. This “paranoid style” of thinking has long shaped political and cultural narratives. Pattern perception, confirmation bias, and epistemic mistrust mixed together make people prone to believe conspiracies, with beliefs persisting even when evidence is weak or contradictory.

This point was personified in August 2025 amid growing speculation that President Trump had died, fuelled by bruising on his hands, a lack of media appearances, and timely Machiavellian comments by JD Vance, sending the internet into a frenzy. Searching for answers, people once again turned to the pizzas. On 30 August, the Pentagon Pizza Index website displayed “Defcon 1”, the highest level of pizza alert. Connecting the slices, the internet concluded – inaccurately – that the commander-in-chief must be dead.

One slice at a time

The Pizza Tracker is not just about pizza. It is about how humans interpret, amplify, and mythologise information. It is about the cognitive biases that shape our thinking and fuel the creation of conspiratorial narratives. Understanding this does not make the phenomenon any less entertaining to follow, but it does remind us of our shared responsibility to separate fact from fiction. More importantly, the rise of ‘Pizzint’ underscores a tension between quality and quantity. The digital era has given us unprecedented access to data, insights, and open-source intelligence. No state or bad actor can easily hide; the vox populi can propel any issue onto the world stage. Yet this abundance comes at a cost, the proliferation of noise. As we advance further into this information-saturated age, we must be careful to scrutinise what may seem, on the surface, to be straightforward, quantifiable, and reliable signals.

For now, we recommend the following:

Treat viral OSINT claims as hypotheses, not conclusions. Patterns observed in open-source data, such as pizza deliveries, should be starting points for inquiry, not proof. Without corroboration, historical baselining, and contextual understanding, even the most compelling pattern risks becoming narrative rather than intelligence.

Build noise-awareness into OSINT practice. The ability to recognise noise is as important as the ability to find signals. This includes acknowledging cognitive biases, resisting novelty-driven analysis, and being wary of interpretations that thrive primarily because they are amusing, alarming, or easily shareable.

On a less serious note, as this is ‘pizzint’ after all, also consider these suggestions:

The US Department of Defence should consider constructing a permanent pizzeria inside the Pentagon, if they have not done so already. That would also help them avoid e.g. the risk of poisoning by malignant actors. Many secure facilities have 24/7 canteens, and you cannot bring in food that you did not make yourself.

As suggested by X user @OTOppressor, the pentagon needs to start designating days where there will be major military strikes as “pack your lunch days”.

What is next

Stay tuned for part II, in which we hope to deliver the actual data to prove or disprove the Pentagon Pizza Theory once and for all. The questions we still want to answer include:

How often do spikes in Pentagon-area pizza orders occur, and how frequently do they coincide with actual military crises? Are pizza spikes observed on regular high-demand days (e.g. Fridays, Saturdays, national events)? How often has pizza delivery volume increased without a military event following? Are there examples of major military decisions or emergency meetings that did not trigger unusual delivery activity? What are some key dates of actual US military operations or security incidents (such as activity around Iran) and can we compare to pizza order volumes?

What are the limitations of public delivery tracker data (e.g. visibility, sampling bias, platform restrictions)? How accurate and consistent are these signals across services (Domino’s, Uber Eats, DoorDash, etc.)? We need to establish baseline data for weekends, sports events, paydays, weather disruptions, and so forth.

And how does all of this compare to other countries, e.g. pizza delivery around Westminster in London or GCHQ in Manchester? We should consider comparative case studies that cover high pizza activity + real event (e.g. pre-Iran strikes in 2025); and high pizza activity + no real event (e.g. Super Bowl weekend).

If you want to work with us to figure this out, then please do get in touch!