EVIDENCE in Action: information disorder workshop

On 16 November 2025, the EVIDENCE network held its first iteration of a mini workshop on combatting CBRN disinformation for students and practitioners. The workshop brought together 40 people in a crisis simulation exercise of various CBRN events. This article is a reflection on the workshop and the value of crisis simulations as an educational tool.

Workshop participants receiving their first ‘intelligence update’ during the mini workshop crisis simulation.

Workshop Background

The workshop involved participants taking on the role of EVIDENCE researchers. They were able to choose from a range of possible positions, such as scientists, academics, journalists and NGO members. The aim in this was to demonstrate the breadth of individuals working in the EVIDENCE network and the range of expertise they bring to our research activities.

Participants were then given information about three fictional countries, each undergoing their own CBRN event. These were:

The Strand Republic: a continental, forest-dense country with a collapsed formal economy. A brutal civil war has fragmented command structures, and a transitional military junta rule the capital while rebel militias command the countryside. These rebel militias have just uncovered an abandoned chemical research facility and reports of the rebels using the gas cannisters found in the facility are beginning to circulate, despite the military denying the footage is real.

The Franklin Islands: an archipelago of volcanic islands in the Southern Hemisphere ruled by an authoritarian technocratic regime that claims scientific supremacy and has advanced oceanographic research facilities and strong naval tech. Volcanic tremors have triggered social media claims that the smoke plume contains radioactive fallout from a secret nuclear submarine test. Citizens circulate homemade “radiation maps” but government remains silent.

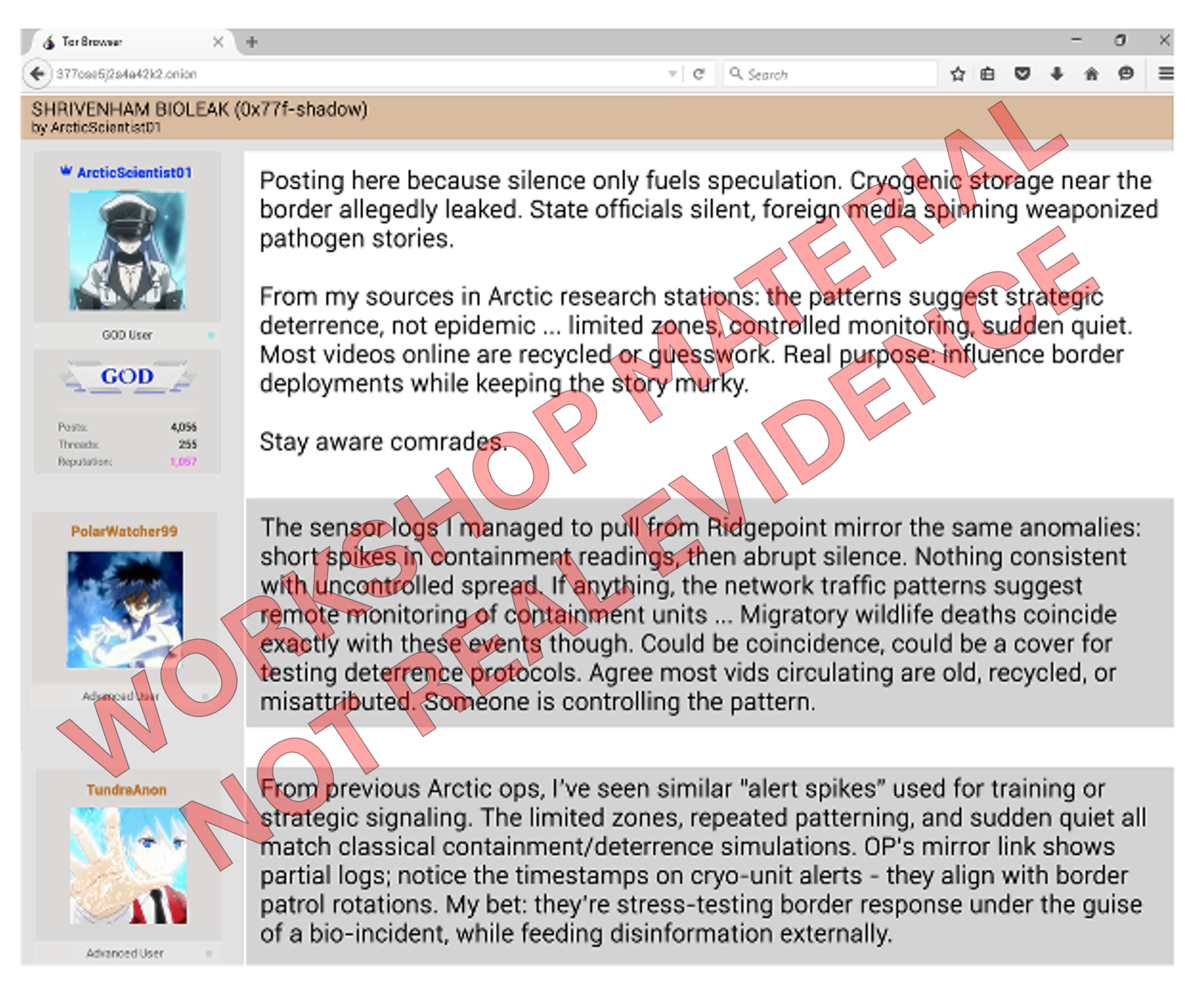

The Shrivenham Territories: a polar territory consisting of small, isolated settlements ruled by a technocratic autocracy that prioritises self-sufficiency and secrecy. The remote Shrivenham Territories have ongoing maritime and territorial disputes with neighbouring Arctic states. Shrivenham scientists report an alleged “bio-leak” from a cryogenic storage facility near the border. State officials issue no comment, while international media speculate about weaponised pathogens.

Participants were assigned one country per group and provided with extensive country background packs, a CBRN backgrounder sheet and a pack of evidence related to their country’s event. They then examined the evidence in their pack and the corresponding information, receiving an interject with an ‘intelligence update’ per nation every 20 minutes. The aim was to engage critically with the evidence and answer a series of questions about the provenance of the information/evidence, what it might mean for their assigned country and how it feeds into the wider issue of CBRN disinformation.

An example of some of the social media evidence provided to participants in the workshop.

Event Recap

Participants started the workshop with a quick introduction to the EVIDENCE network and its activities. They were then assigned their fictional countries – as we had six tables, the groups were split into two tables per country. The participants were given their materials and had a few minutes to examine the packs before the first interject came. This first interject was part of a so-called ‘uncertainty phase,’ during which incidents first come to light and information is incomplete, so rumours spread quickly.

The Franklin Islands teams - who had received messages about social media reports mentioning nuclear signatures in the reported volcanic eruption - began identifying discrepancies in the ‘satellite data’ being shared. They discussed how experts could verify this information. Teams focusing on the Strand Republic started thinking critically about posts on X coming from ‘experts’ commenting on the situation. They examined how to verify the identity of those claiming to have insight into the truth behind the reported use of chemical agents. The Shrivenham Territories teams reflected on the silence from government officials and how this strategy allows competing narratives to form. They recognised the uncertainty this can create and the importance of verifying information and considering different perspectives in this information landscape.

Workshop participants discussing the contents of their evidence packs.

With the second interject, teams entered the ‘crisis phase’ – where competing narratives multiply, leading to false evidence, doctored data and emotional content. The Stand Republic update reported that a rebel spokesperson released a “scientific report” alleging the government used chlorine gas. It appears professionally formatted but the data is clearly fabricated. From the Franklin Islands, a viral video showed a “black soot cloud” allegedly from a nuclear mishap – satellite data contradicted this, but the video dominated local feeds. Finally, in the Shrivenham Territories, an anonymous whistleblower leaks “government documents” claiming the cryogenic virus was engineered for territorial retaliation. No independent verification of this claim was available.

Extract from participant feedback: “It’s important to ask ‘how do you know?’”

Teams from the Strand noted the importance of checking the fabricated data and how they could communicate its falsity to audiences in a timely manner. Franklin Islands teams discussed what motivations actors might have in disseminating fake videos and what markers they could encourage people to look for when they are faced with videos claiming to show certain evidence. Shrivenham Territories teams reflected on the fact that the government was in dispute with neighbouring countries, and how reports from an ‘anonymous whistleblower’ may have to be treated with the potential of foreign interference.

The final interject signalled the start of the ‘credibility phase,’ as the immediate crisis fades - and the teams had to think about the aftermath of the events and how trust might be eroded by this point.

A group of participants reflect on the final interject.

In their final update, participants learned that in the Strand Republic, international journalists have revealed that some rebel claims were partly true – chemical traces are confirmed, but evidence was exaggerated and foreign aid agencies are hesitant to intervene. In the Franklin Islands, scientific data confirms the event was purely volcanic but online “radiation” theories persist, influencing tourism and trade. Finally, in the Shrivenham territories, a global health NGO confirms no weaponised virus existed, but global trust in Arctic research collapses and international collaborations are suspended.

Extract from participant feedback: “The workshop led to discussions about processes I’d never considered before.”

All teams reflected on the speed with which the information landscape can change and how disinformation can radically impact trust in an institution. They also discussed how navigating this information landscape would be difficult for the average citizen and how poor or absent communication can be weaponised to mislead the public. This led to some productive conversations about tactics to combat disinformation, including the importance of putting out timely and accurate information, and training the general public on how to recognise fake evidence.

Crisis Simulations as an Educational Tool

Simulations are a widely accepted pedagogical tool, allowing individuals to practice complex skills and apply theoretical concepts while immersing themselves in a particular environment. It can also help individuals feel more connected to and invested in the material they are engaging with, which can be useful when trying to promote an objective or concept.

Wargames, for example, are commonly employed in classrooms, military academies, companies and even international organisations as a tool to simulate major events, conflicts and crises. The Wargaming Network at King’s College London engages in extensive research on the use of such games for learning and teaching purposes. Research from simulations run at Richmond American University London also reveal that crisis simulations are useful in helping participants develop adaptive decision-making, cross-sector negotiation and strategic communication skills, whilst promoting empathy and collaborative problem-solving.

These outcomes can be particularly useful when it comes to EVIDENCE’s goal of combatting disinformation and promoting healthy information landscapes. Allowing audiences to experience how a CBRN disinformation crisis can unfold first-hand and how decision making within such a crisis can impact trust and credibility thereafter can be useful tools to raise awareness.

Workshop Outcomes: What’s Next

Most participants noted the utility of the workshop in helping them think about CBRN disinformation in a new light and about the complexities of engaging with fake evidence.

Building on the feedback and outcomes of this workshop, the EVIDENCE Network aims to develop a suite of tools and materials to support future CBRN disinformation simulation exercises. These include expanded and tiered simulation formats tailored to different audiences, from students and early-career researchers to practitioners working in policy, media, and emergency response settings. Alongside this, the Network plans to produce facilitator toolkits and participant resources to enable the wider use and adaptation of these exercises across institutional and regional contexts. We are also exploring opportunities for digital and hybrid delivery, incorporating interactive evidence packs. By refining and scaling this approach, EVIDENCE seeks to strengthen capacity to recognise, analyse, and respond to CBRN disinformation across a range of professional and public settings.

To stay up to date with other events like this in the future, sign up to our mailing list and consider following our LinkedIn page!

The event organisers would like to thank Michael Abrahams, James Brady and Colette Dauchez for their assistance in facilitating this workshop. The Network would also like to thank the King’s SSPP Research Culture Fund for making this workshop possible.